Who was Henry VIII behind the mask of power, and what was his legacy? Historians discuss many different versions of the king, from a domineering would-be tyrant to a man desperate to be liked and vulnerable to the influence of others.

Here we explore some of Henry’s consistent passions: his love for hunting, which took him on a series of progresses across southern England; his relationships with women, complex and frighteningly violent but also capable of devotion; and his obsessive acquisition of luxury goods, from tapestries and jewels to sumptuous clothes and clockwork toys.

Following the death of Henry’s son Edward VI (ruled 1547-53) aged just fifteen, the power and prestige of the Tudor crown were inherited by his two daughters: first Mary (ruled 1553-58), devotedly Catholic in honour of her mother and defiance of her father; and then Elizabeth (ruled 1558-1603), whose achievements and fame today exceed those even of Henry VIII.

The wealth of a Tudor King

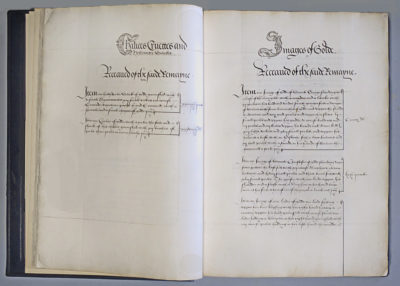

This exceptional document is the first of two volumes inventorying the belongings of King Henry VIII….Read more➜

The wealth of a Tudor King

- Reference Number:

- MSS/0129/A

- Object Name:

- Manuscript

- Description:

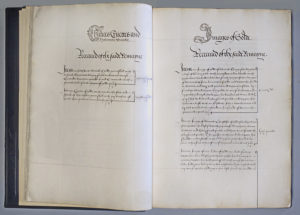

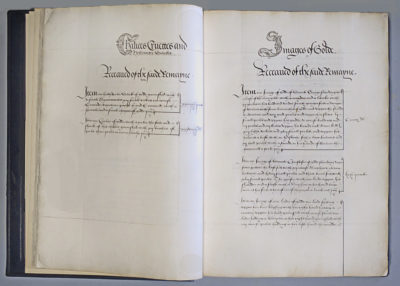

This exceptional document is the first of two volumes inventorying the belongings of King Henry VIII.

On 28 January 1547, Henry VIII died in his bedchamber at the Palace of Whitehall, aged 55. As part of the arrangements for Edward VI’s minority, commissioners were appointed to draw up an inventory of Henry’s movable goods and the contents of his 55 palaces. Compiled between 1547 and 1548, the resulting inventory had 17,810 entries including clothes, furs, jewels, furnishings, ships, chapel goods, and riding gear. Henry spent more on his palaces than any monarch that had come before and had amassed so many beautiful things that the inventory took 18 months to complete. The result was so large that it had to be bound into two volumes. The first of these volumes is what you see here.

When first compiled, the inventory allowed the keepers of the King’s possessions to keep track of the objects placed in their charge. It has now become a significant source for historians who wish to analyse the wealth, magnificence, and material culture of Henry VIII’s court and that of his children.

The document tells us how household ordinances were implemented; how the liturgical year was observed; and how Henry had passed the contents of the queen’s coffer on from one wife to the next! The inventory also provides a valuable insight into the private life of England’s most notorious monarch. The inventory details the layout of the King’s apartments at his Palaces of Whitehall and Greenwich and provides details of the King’s 21 removing coffers. These were the travel chests that went with the King when he travelled out on progress, campaigns, and state visits. His glasses, medicines, reading material, and keys travelled with him wherever he went. Intriguingly, Henry also travelled with a copy of his Assertio Septem Sacramentorum, the defence of the Catholic church that had earned him the title of ‘Defended of the Faith’.

- Maker:

- Production Place:

- England

- Materials:

- Ink on paper

- Date:

- 14 September 1547

- Dimensions:

- Provenance:

- Purchased for the Society of Antiquaries by John Topham, Treasurer SA, from Brander’s sale, 8-13 February 1790, lot. 1164.

- License:

The importance of appearance

This manuscript is ‘A Booke or Inventorie of the Remaine of his Majesties Warderobe Stuffe, Ornaments of Howsehold … Remaineing now at Denmarke Howse …’….Read more➜

The importance of appearance

- Reference Number:

- MSS/0137

- Object Name:

- Manuscript

- Description:

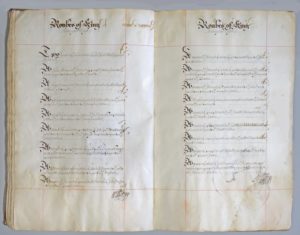

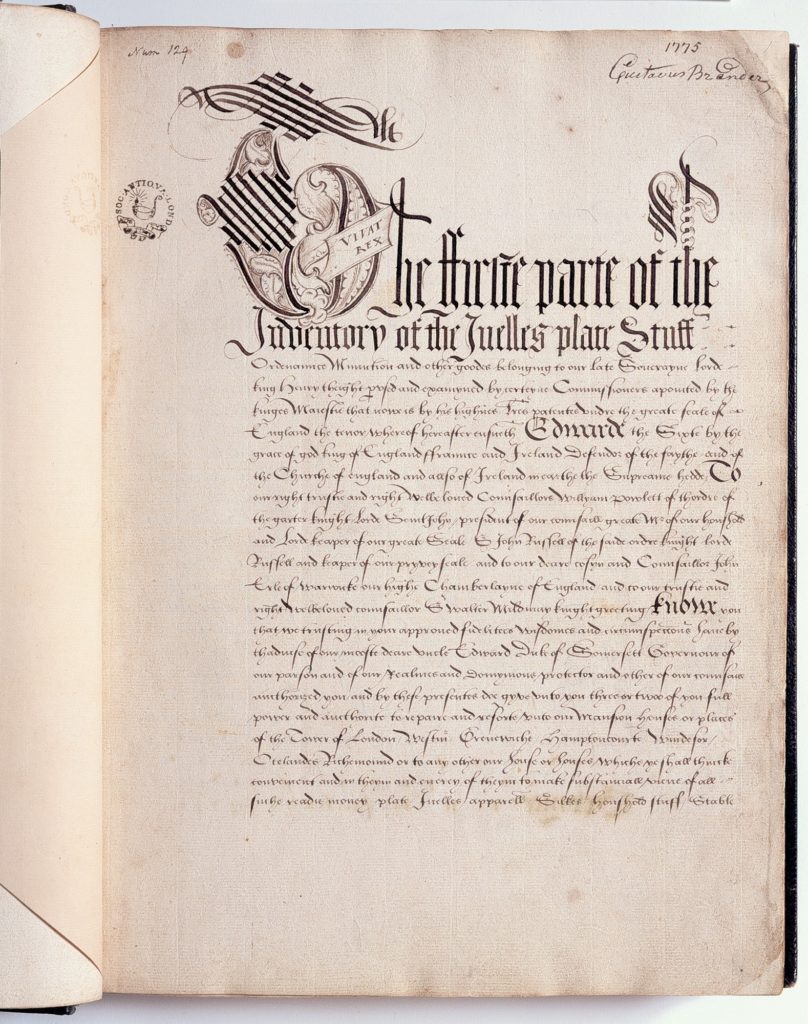

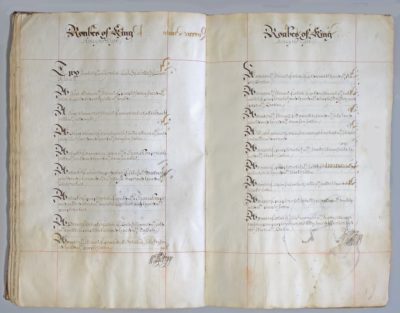

This manuscript is ‘A Booke or Inventorie of the Remaine of his Majesties Warderobe Stuffe, Ornaments of Howsehold … Remaineing now at Denmarke Howse …’. The contents of the wardrobe had been in the custody of Richard Browne, Keeper of His Majesties Standing Wardrobe. The clothes remaining in the wardrobe at Denmark House (where Somerset House, London, now stands) were inventoried in 1627, during the reign of Charles I (r.1625-1649), by his own Clerk of Wardrobe, William George, and this manuscript was the result.

The inventory includes details of arras (finely woven tapestries from Arras, Norther France) and wall-hangings, details of the robes of Henry VIII, and details of the parliament robes of Anne of Denmark (consort to James I). The entries listed under ‘Robes of King Henry the Eighth’ provide us a glimpse of the care the King took to ensure that his personal magnificence transmitted power, and inspired awe. There is various mention of cloth of purple (a royal colour that was off-limits to all but the King); cloth of silver; and cloth of gold; and several robes combining all three. Some robes were lined with fur, draped with a Spanish cape, or decorated with twists of gold. It is no wonder that his subjects stood in awe of their King and trembled in his presence.

- Maker:

- Richard Browne

- Production Place:

- Denmark House (now Senate House), London, England

- Materials:

- Vellum-bound ink on paper

- Date:

- 1627

- Dimensions:

- Provenance:

- Found in the ‘old part’ of Somerset House before demolition in 1786. Presented to the Society of Antiquaries by Sir William Chambers, 12 January 1786

- License:

The last will and testament

This is the Society’s copy of the last will and testament of Henry VIII, drawn up in December 1546, before his death at Whitehall Palace on 28 January 1547….Read more➜

The last will and testament

- Reference Number:

- MSS/0249

- Object Name:

- Manuscript

- Description:

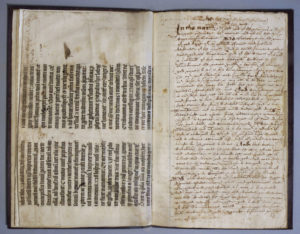

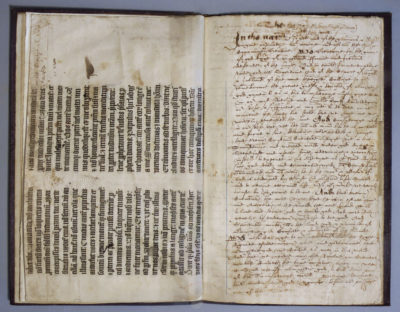

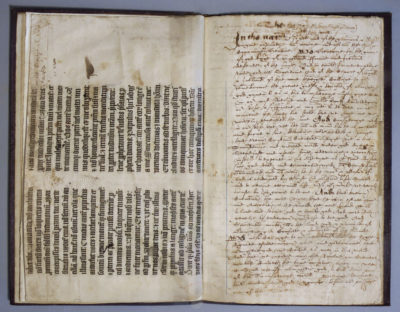

This is the Society’s copy of the last will and testament of Henry VIII, drawn up in December 1546, before his death at Whitehall Palace on 28 January 1547. Our copy is written in the hand of John Godsalve (1505-1556), who was a clerk of the signet to King Henry VIII. Godsalve was later knighted at the coronation of Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, and went on to become one of the most trusted councillors of Mary I’s court.

To understand the importance of Henry’s will, we must first understand Henry’s Acts of Succession. The first Act, in 1536, had declared his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to be illegitimate. It stripped them of their title of ‘Princess’ and blocked them both from the throne, leaving Henry without an heir. His hopes lay with his new wife Jane Seymour, and the Act named her children or the children of any wife that followed her, as his successor. By the time the 1544 Act of Succession was issued, Jane Seymour had given birth to Edward. He was named as heir, with Mary and Elizabeth re-instated (but not re-legitimized) after their half-brother.

The later Act still gave Henry ‘full and plenary power and authority to give, dispose, appoint, assign, declare, and limit [the succession], by your letters patents under your great seal or else by your last will made in writing and signed by your most gracious hand’. This granted Henry the right to appoint his successor in his will, so deciding the future of the country. Henry’s power would thus continue even after his death. No royal will had done this before.

When, on the 30 December 1546 Henry’s final will was drawn up and stamped, it was indeed his nine-year-old son Edward who was appointed as his successor. Henry also named the regency council who were to support Edward during his minority. Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset was named as ‘Lord Protector of England’. Edward VI acceded to the throne, as ‘King of England, Ireland, and France, Defender of the Faith and Supreme Head of the Church of England’. Henry’s will was dedicated, as his life had been, to ensuring the succession and the continuation of the Tudor dynasty.

This document is extraordinary for another reason. Throughout Henry’s life he had remained a pious man despite all that had come to pass. Henry dedicated the opening lines of his will to the ‘blessed Mother ever Virgin, our Lady Saint Mary’. He goes on to state that he was born to sin, as all mortal men are; he acknowledges his belief in transubstantiation; he leaves land to the church in exchange for daily prayers for his soul; and he ‘most humbly and heartily’ bequeaths his soul to God. Henry’s public policies had triggered the English Reformation, but Henry’s private faith had remained distinctly Catholic.

- Maker:

- John Godsalve

- Production Place:

- England

- Materials:

- Vellum and cloth-bound ink on paper

- Date:

- c. 1547

- Dimensions:

- Provenance:

- Discovered by Samuel Woodward (1790-1838) among old deeds of the Bedingham estate, Norfolk, and presented to him by Clement Unshank. Given to the Society of Antiquaries by Bernard Bolinbroke Woodward FSA (son on Samual Woodward), 15 June 1865.

- License:

A return to Catholicism

This portrait of Mary I (r. 1553-1558) was the first major portrait to be painted shortly after her coronation, some time around her 38th birthday, and before her marriage in July 1554 to Philip (later Philip II) of Spain.

…Read more➜

A return to Catholicism

- Reference Number:

- LDSAL336

- Object Name:

- Painting

- Brief Description:

This portrait of Mary I (r. 1553-1558) was the first major portrait to be painted shortly after her coronation, some time around her 38th birthday, and before her marriage in July 1554 to Philip (later Philip II) of Spain.

- Description:

This portrait of Mary I (r. 1553-1558) was the first major portrait to be painted shortly after her coronation, some time around her 38th birthday, and before her marriage in July 1554 to Philip (later Philip II) of Spain.

Mary, like her father, recognised the importance of image as a means of communicating power and after visiting the English Court, Venetian Ambassador Giacomo Soranza wrote that ‘[Mary] seems to delight above all in arraying herself elegantly and magnificently’. Here she wears cloth of gold and cloth of silver, embroidered with gold thread, and encrusted with diamonds and pearls. She, like her father, also favoured the works of leading continental artists, surrounding herself with prominent painters, poets, writers, and musicians. She chose recently arrived Netherlandish artist Hans Eworth to paint this first official portrait, with Eworth painting Mary in the demure pose often used for women, even of the highest status, in the early sixteenth century. Hans Eworth is now recognised as the most distinguished foreign painter in Tudor England after Hans Holbein.

Mary was the daughter of Henry and his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, and was a devoted catholic, as her mother had been. The jewels worn for this portrait sitting were carefully chosen to demonstrate her catholic faith. She wears a distinctive Tau (headless cross) at her neck and from her waist hangs a reliquary of the four Evangelists, with the latter having belonged to her mother. She had found this in the Treasury, broken, and had had it repaired for her own use.

Henry had never intended that Mary should come to the throne and had instead supposed that his son, Edward VI, would bear his own heirs, but Edward had died at fifteen after contracting tuberculosis. Edward and his council, realising that his death was imminent, had attempted to block his Catholic half-sister’s accession to the throne by placing Lady Jane Grey in her place. However, Mary’s public popularity meant that council were forced to reverse this decision just nine days later.

During Mary’s short reign she attempted to reverse the Reformation in England that had been started by her father and managed to achieve reconciliation with the Catholic Church. Despite her efforts, she was largely unsuccessful in her attempts to restore Roman Catholicism to England and her marriage and the policy of burning heretics saw her initial popularity decrease during the course of her reign. She died without heir and the crown passed to her half-sister, protestant Elizabeth I.

- Maker:

- Hans Eworth (1520-1574)

- Production Place:

- England

- Materials:

- Oil on oak panel

- Date:

- 1554

- Dimensions:

- H1040mm W780mm

- Provenance:

- Kerrich bequest of 1828

- License:

The Catholic Court of Mary I

The illuminated title page displayed here, belongs to Mary I’s Book of Fees and Offices that was drawn up almost immediately on her ascension to the throne in 1553….Read more➜

The Catholic Court of Mary I

- Reference Number:

- MSS/0125

- Object Name:

- Manuscrpit

- Description:

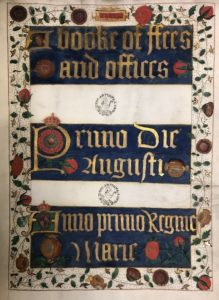

The illuminated title page displayed here, belongs to Mary I’s Book of Fees and Offices that was drawn up almost immediately on her ascension to the throne in 1553. The page is richly decorated with royal Tudor iconography: The Crown of England, the Royal Arms, and The Tudor rose. Among these established and recognisable symbols of Tudor monarchy can be found five beautifully detailed pomegranates. The pomegranate was the personal symbol of Katherine of Aragon, Henry the VIII’s first wife and Mary’s mother and may have been used by Mary to recall and honour the memory of her mother and to conjure up memories of the Catholic Court that had been present under the rule of her mother and father, before the break with Rome.

The document gives a detailed account of the names, offices, and fees of Crown officials who served Mary I at court and across the country – the network of officials she relied on to rouse support, establish law and maintain control as she reintroduced Catholicism to her kingdom. The Booke of Ffees and offices also allowed her to identify and put on notice all those who may waver in their support- those who had supported the protestant cause previously. Mary was establishing a Catholic Court and country and she had to be sure that those who were closest to her could be trusted to support her in her ambitions.

The content of this manuscript also allows a glimpse at the continuing splendour and magnificence of the Tudor court with musicians, composers, revellers, poets, harriers, hounds-men, and groomsmen being among those employed in the household of Queen Mary I. Mary may have differed from her father in her religious beliefs but from him she had learnt the importance of displays of power and magnificence as propaganda.

Mary reigned for just 5 years and died without heir on the 17th November, 1558.

- Maker:

- Production Place:

- England

- Materials:

- Cloth-bound ink on paper and vellum

- Date:

- 1553

- Dimensions:

- Provenance:

- License:

A Tudor title and modern monarchy

Seen here is an engraved colour copy taken from a miniature of Elizabeth I, designed by Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), and stored in the collection at Ham House….Read more➜

A Tudor title and modern monarchy

- Reference Number:

- SAL31509

- Object Name:

- Printed book

- Description:

Seen here is an engraved colour copy taken from a miniature of Elizabeth I, designed by Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), and stored in the collection at Ham House. The miniature is just one of many that were produced from Hillard’s portrait, and these would be purchased and worn by Elizabeth’s subjects who wished to show loyalty to their queen. Our engraving appears in the 19th Century volume Queen Elizabeth, authored by The Right Reverend Mandell Creighton.

Below this is Elizabeth I’s second Great Seal, designed by Nicholas Hilliard 1584. Hilliard worked with Derrick Anthony, chief engraver of the Mint, to produce a new silver seal matrix from which this wax impression was made. The images on both sides – of the monarch in ‘majesty’ and as equestrian warrior – were approved by the Queen. The detailed representations of her horse, costume, badges, and regalia, testify to Hilliard’s great skill as a designer, and around the edge runs the legend: ELIZABETHA DEI GRACIA ANGLIE FRANCIE ET HIBERNIE REGINA FIDEI DEFENSOR – ‘Elizabeth, by the Grace of God, Queen of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith’. The seal came into use in 1586.

When the Catholic Queen Mary died without heir, the throne passed to her half-sister Elizabeth, in line with the succession as outlined in Henry VIII’s will. Her accession marked another drastic change for English religion. The protestant Elizabeth was quick to re-establish a protestant court and quick in attempting to reverse the policies of her Catholic half-sister. An Act of Supremacy saw Elizabeth titled ‘Supreme Governor of the Church’, much like her Father’s title of ‘Supreme Head’, and early in her reign she issued a proclamation ordering the re-introduction of English Prayer. The 1559 Act of Uniformity ensured that English worship followed the Book of Common Prayer, and English Bibles were re-instated in churches, whilst orders were issued for images and idols be torn down. Like her father, Elizabeth deployed commissioners to tour the kingdom ensuring that her edicts were followed by the clergy, but scrutiny of this kind did not last, and some traditional practices continued or were retained and absorbed into the new form of English post-Reformation religion.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Elizabeth had been excommunicated by the Pope, and England had ceased to be a Catholic country once again and so Elizabeth, like her father before her, was both Supreme Governor of the Church in England and Defender of the [Anglican] Faith. When in 1603 Elizabeth died without heir, the Tudor dynasty ended, but the title of Fidei Defensor- gained, lost, and re-imagined by her father- and the title of Supreme Head of the Church, passed on. The titles have been passed to and used by every English monarch since.

- Maker:

- Miniature designed by Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619); Author Reverend Mandell Creighton (1843-1901); Published by Boussod, Valadon & Co

- Production Place:

- London, England

- Materials:

- Ink on paper

- Date:

- Miniature c.1590; facsimile 1896

- Dimensions:

- Provenance:

- License:

/